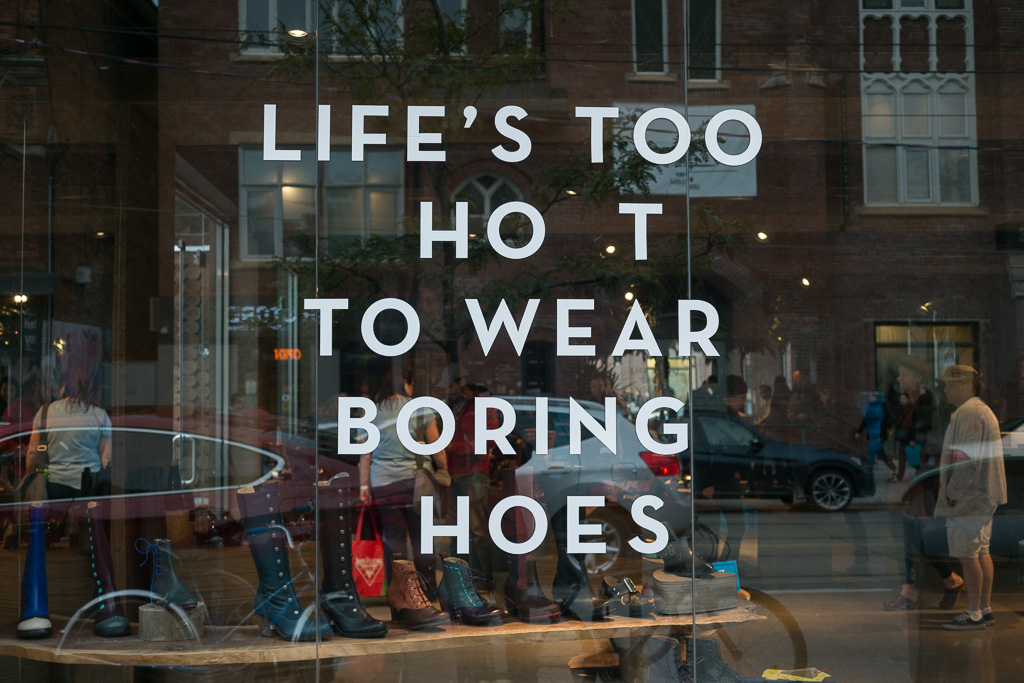

It’s dead on a Friday afternoon in the city. After the May long weekend, all the Gen-Xers head up north to open the cottages they’ve inherited from parents now laid out in Mount Pleasant Cemetery. The Millennial kids don’t go with; they can’t imagine a worse way to spend a weekend than stuck on a gravel cul de sac, no dock in the lake, water too cold for swimming, and the air swarming with black flies. It’s better being stuck bored in town where at least they can make a run to Tokyo Smoke.

After a couple joints, they remember the angel standing guard over granddad’s grave. They call a couple buddies from school, the ones who haven’t turned domestic yet, and invite them over to do some wingsuit base jumping from their 50th floor balcony. A thousand years ago, we could only imagine what it must be like to wheel around the heavens, cherubim and seraphim sailing to glory on a wing. Now look at us.

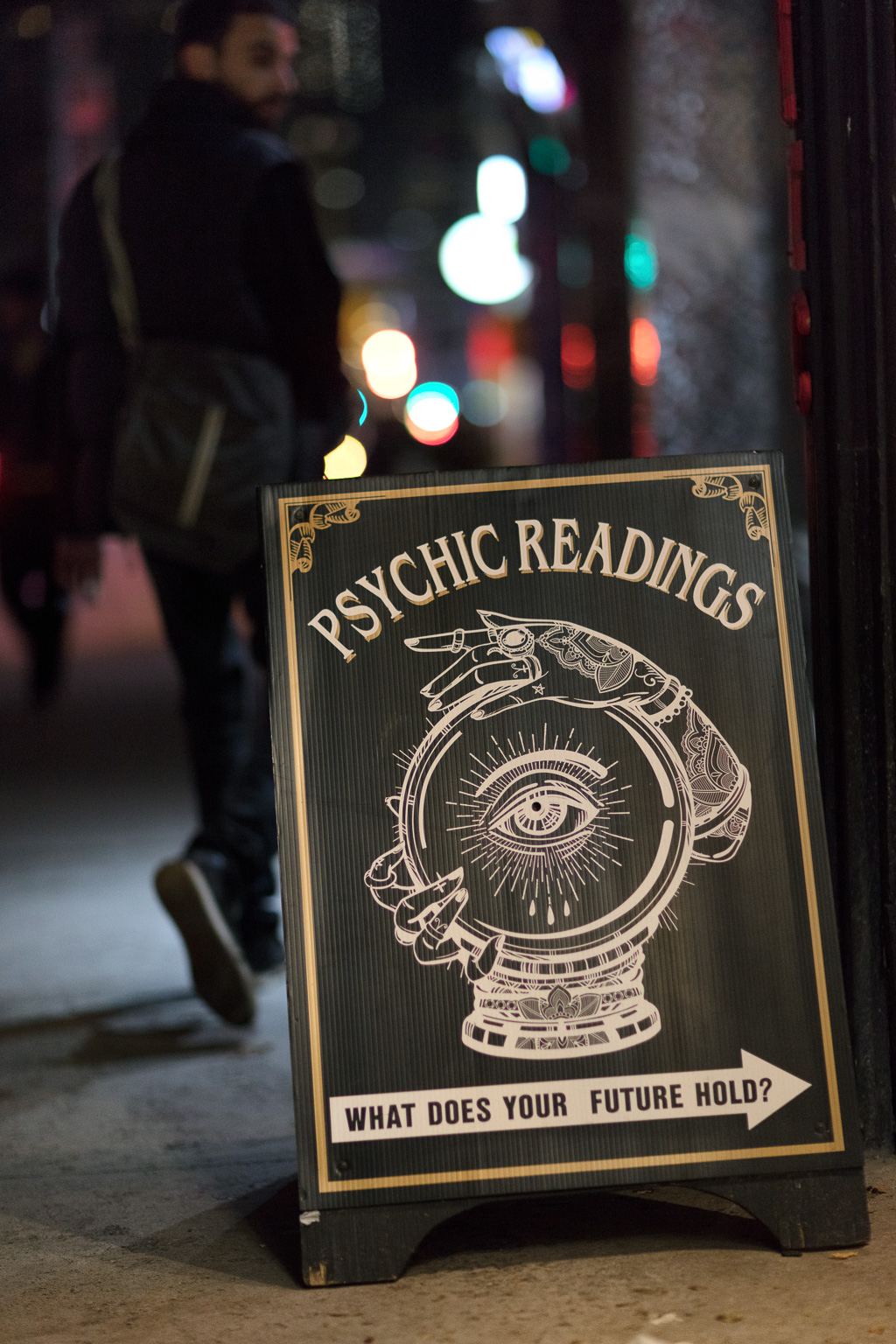

Most of the friends say they’re busy, but at least one of the friends has the guts to offer the excuse all the others are thinking: you’re a lunatic. And maybe that’s true. But the divide between lunacy and holiness is paper thin. They used to say that someone whose behaviour was a bit off was “touched” as if to suggest that they’d been touched by the holy spirit. Because authorities weren’t confident they could tell which side of the divide a person stood on, they conflated the two sides and called the person a holy fool.

Years ago, when it was still fun to go to the cottage, they’d stand on the dock, toes curled around the rough edges of the pressure treated wood, arms pulled back in preparation for the leap. Always, there was a pause. Time hanging still in the summer air. They could feel the splash of the cold water even before it struck the skin. They could sense the approach of the dark nothing that would enfold them as they sank below the surface.

That leap was a perfect moment, poised in flight, held between sky and water, memory and oblivion. Only a couple friends come over, and then, only to watch. Everyone else is busy adulting. Everyone else has already sunk like a stone and the water grows dark overhead.