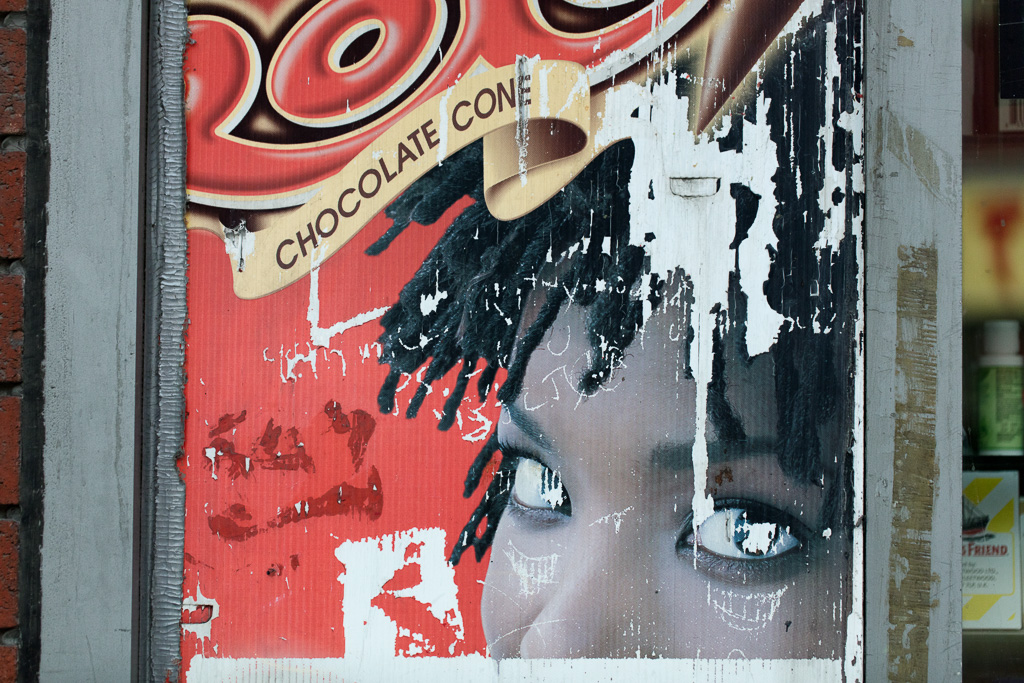

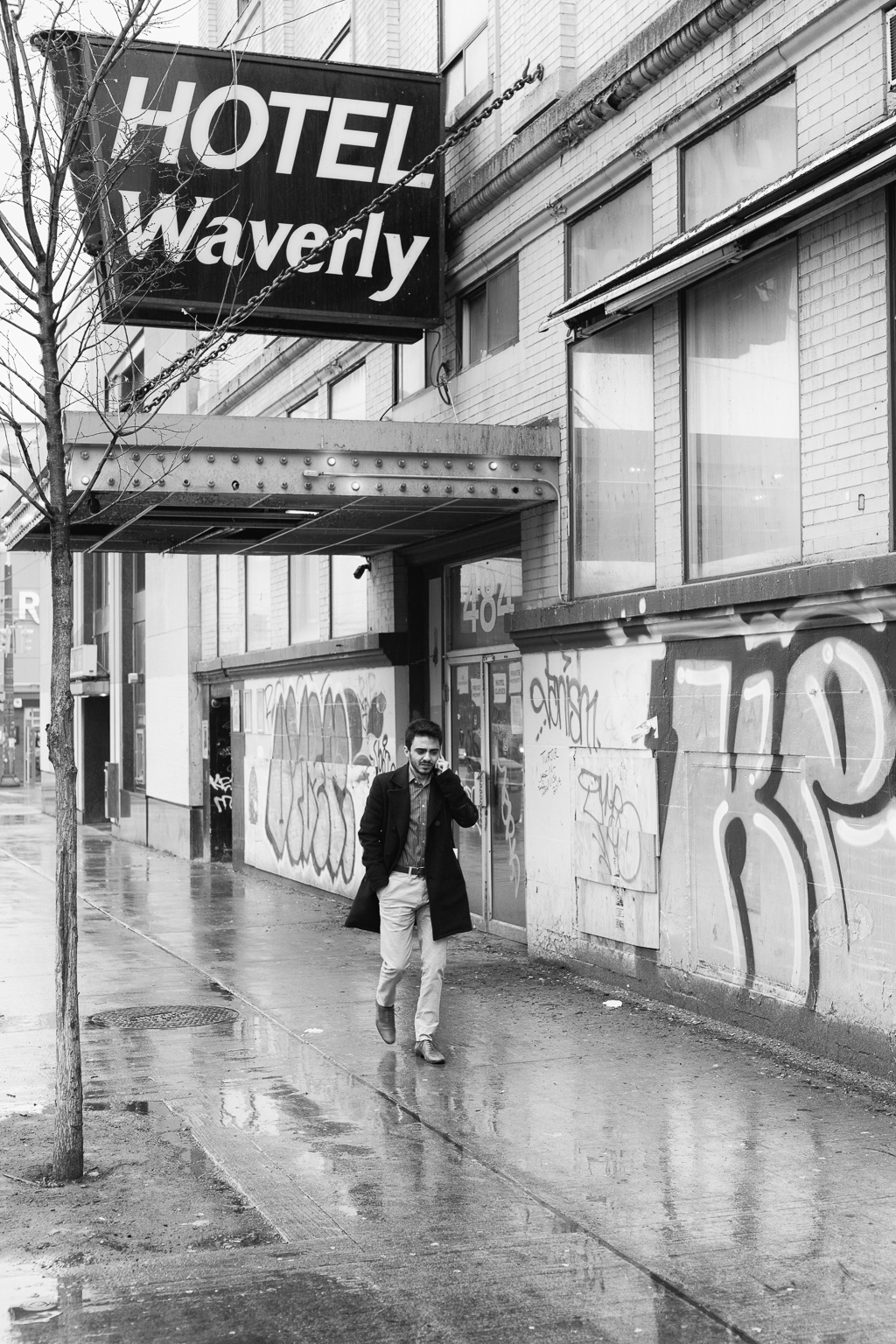

I confess: I’m responsible for rumours of a lost Basquiat. I’d written a story about how Basquiat painted a fence and I posted the story on my website. It turns out there are a lot of people who can’t tell the difference between a story (work of fiction) and a story (piece of news). I’m not sure the difference is all that meaningful, but that’s another story. In any event, my story (work of fiction) sprouted legs and skittered into the shadowy reaches of the internet where it got quoted as god’s awful truth in threads about neo-expressionism. Faster than you can say “by-line”, somebody on Wikipedia posted a link to my story (work of fiction) as evidence for the existence of a lost masterpiece. Given that a Basquiat sold in 2017 for $110.5 million, you can understand why the hunt for a lost Basquiat turned into the art world’s equivalent of a gold rush. People flocked to the Lower East Side, pulling up graffiti covered fence slats and inundating galleries with demands for authentication.

I took down my website at the beginning of the pandemic because I got tired of all the questions coming through my contact form. In retrospect, it was naive to assume that most people have the fiction version of gaydar that automatically alerts them when they’re reading fiction even when it masquerades as reportage. Anyways, to my story. As I say, I took down the website, so my story has gone missing even on websites like the Internet Archive with its Way Back Machine. But I remember how it went, so here it is in broad strokes:

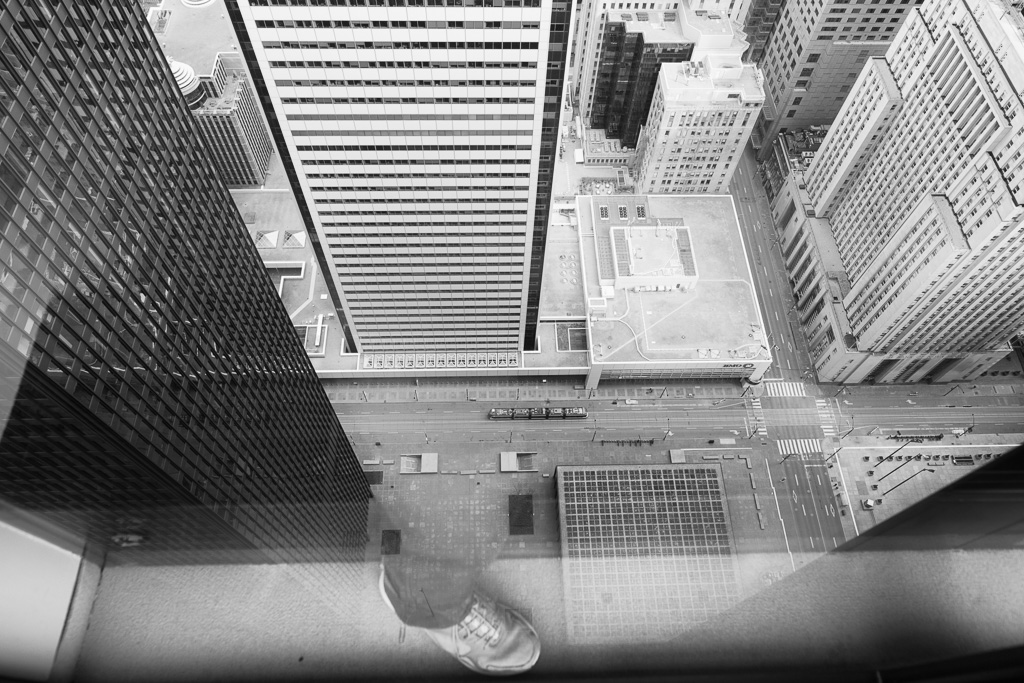

In the mid 80’s, when Ronald Reagan was still using shoe polish to colour his hair and Oliver North was still siphoning money to the Contras in Nicaragua, Jean-Michel Basquiat shot up in a 3rd floor tenement apartment on the Lower East Side. The owner of the apartment wanted to watch TV but the young artist was splayed across his favourite spot on the couch so the owner dragged him onto the fire escape and forgot about him. Almost a full day later, Basquiat woke to the sound of a basketball banging on the pavement of the parking lot below. A refreshing breeze cooled his body. Slivers of light fell through the ironwork of the fire escape and settled on his face. Like pigeons taking flight, laughter rose up from the parking lot. And, for a few minutes at least, Basquiat was happy. He felt gratitude. Like St. John of the Cross, he had known his dark night of the soul and now he lay on the metal landing, safe and awake and free from the harrowing.

Struggling to his feet, Basquiat leaned on the railing and watched the kids shooting hoops. The far side of the parking lot was bounded by a plain wooden fence and, at least in Basquiat’s mind, its plainness cried out to him the way a blank canvas cries out for paint. Its plainness was a blight. Its plainness was an insult to the joy of the kids running layups in the sunlight. He crawled back through the window where he found his canvas shoulder bag full of spray paints and he stumbled downstairs. He would thank the kids by turning their fence into a testament to their joy.

It wasn’t long afterwards that the artist OD’d and, as always seems to happen, Death strolled through all the galleries of Manhattan, waving a bony finger and converting Basquiat’s art into money. But Death forgot to wave a bony finger as he passed the parking lot where the late artist had lately spray painted his message of gratitude and joy, so the owner of the tenement building, (mis)taking it for vandalism, painted over it with a dull grey wash. And there the painting lay, hidden beneath a soul-deadening layer of paint and accumulating grime, on through HIV/AIDS, and the Gulf War, and 9/11, and the invasion of Afghanistan, and the collapse of the Lehman Bros., and the election of Obama, and the defeat of Clinton at the hands of an overblown grifter, and the arrival of Covid-19, and rants about a stolen election. All these layers of misery laid down over a single fleeting moment of gratitude.

And that was my story. Or at least the gist of it. As I say, I took the original down and it’s since disappeared. If I rewrote the story, not as fiction but as reportage, and I scraped away all the layers of this historic palimpsest, I’m not sure I’d ever come to a sunny day in Basquiat’s youth when a wave of gratitude and joy swept over him. That is the fiction. As reportage, I’m inclined to think I’d find misery all the way down to that very first needle in the arm, maybe even down into the cradle. The idea that he might once have known joy: that is the lost Basquiat.