Coming out of the pandemic, I had great hopes. I entertained a fantasy that, as a society, we would engage in serious introspection, we would learn valuable lessons, and then we would apply those valuable lessons to other areas of our collective life. Just imagine, I thought to myself, if the pandemic’s lessons in epidemiology could provide us with transferable skills, like an understanding of how exponential growth works, or how statistical modelling can help us understand the consequences of collective behaviours.

But here we are! On the down slope of the 6th wave. With no guarantee that there won’t be a 7th wave (although Sting tells us that love is the 7th wave). And no guarantee that we have the stomach to do anything about it even if there is a 7th wave. While I understand that people feel frustrated and worn out, I also recognize that what we have faced—a pathogen—does not reason, does not negotiate, and does not favour one ideology over another. All we have in answer to it is a commitment to apply public health principles and a willingness to learn as we go. For me, that means getting all the vaccinations to which I am entitled, wearing a mask indoors where necessary, and avoiding large indoor crowds of unmasked people. Ideally, I place myself in proximity to people who share my approach so that we can be mutually supportive.

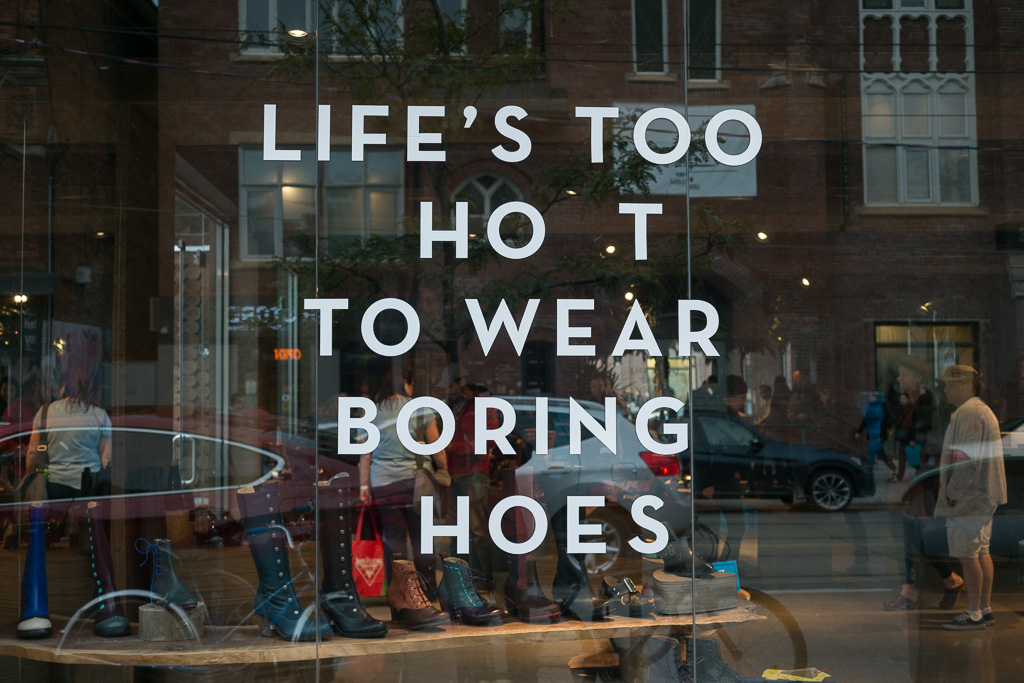

Unfortunately, a pathogen is the least of our worries. There are things we do to ourselves that pose a far greater threat. However, these other things play out on a timeline that allows us to be distracted by more immediate concerns. Consumerism is a fine example of a threat that routinely stymies our collective imagination. We are smart people, aren’t we? It should be no problem to apply our lessons about exponents and statistics. It’s a straightforward thing to extrapolate from a few bags of consumer waste to a situation in which the oceans bloat with plastic and microplastics circulate in the bloodstreams of every living creature on the planet, including you and me. This doesn’t even take imagination. All it takes is a pencil and a calculator.

You think wearing a mask is an inconvenience? Jesus fucking Christ, wait’ll you see what’s coming 20 years from now. We’ll remember these as the good old days.