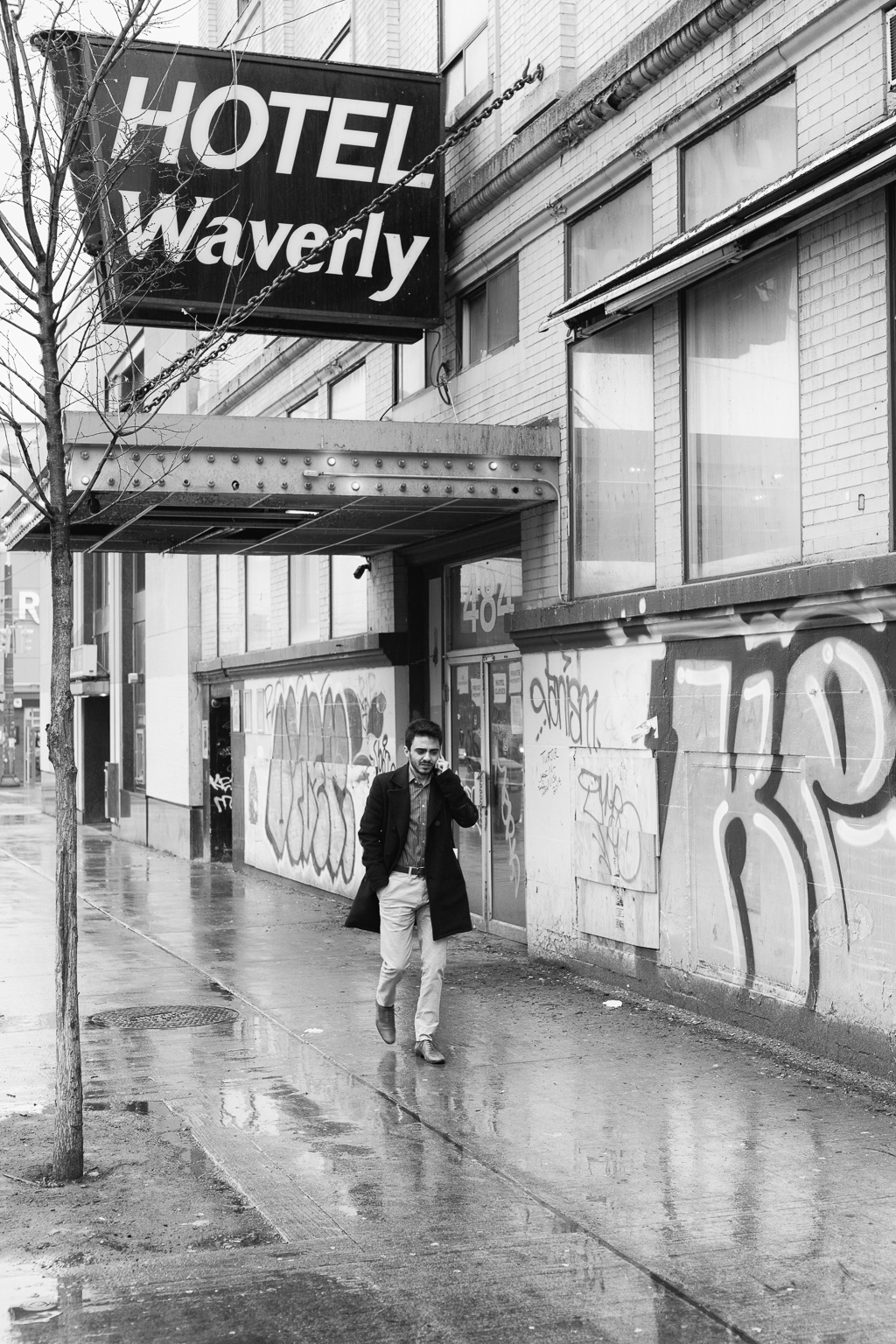

There is a kind of street photograph that I try to avoid at all costs. It’s the “catch whatever’s walking down the sidewalk” photograph. People being people. People going to work. People going home from work. People waiting for the light to change. People walking at night. People walking in the morning. People walking in dull light. People walking in bright light.

Yawn.

I prefer to capture people engaged in interactions either with other people or with their environment. People kissing people. People yelling at people. People avoiding puddles. People protesting things that make them angry. People spray painting messages on walls.

In the first case, I could photograph a cardboard cutout on the sidewalk and you wouldn’t be able to say for certain whether it was a flesh-and-blood person or a poster from the print shop. In the second case, my photograph would capture a dramatic encounter impossible to replicate no matter how many times I revisited the scene.

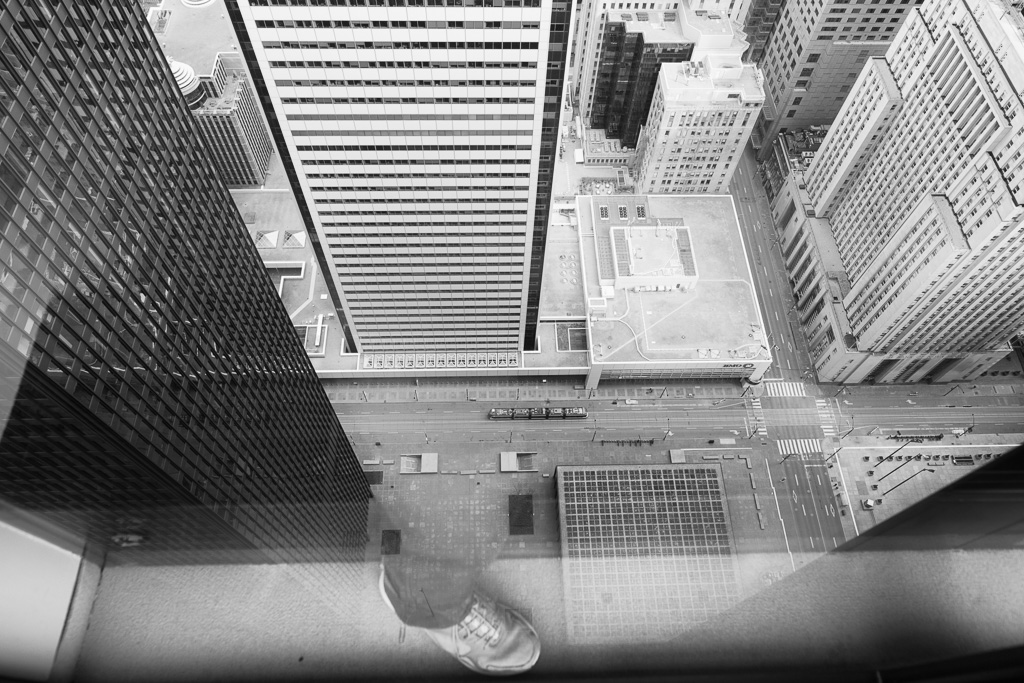

However, every rule has its exceptions, as does the rule about photographing people only when they’re engaged in interactions. In today’s photograph, a man offers a pamphlet to a passing woman who emphatically ignores him. This documents a deliberate refusal to engage.

In a way, this encounter typifies all contemporary public discourse. Never have so many people had so much to say. And, thanks to universal literacy and social media, never have so many people had the means to disseminate their messages. At the same time, never have so many people found themselves the unwilling audience for so many messages. Never have so many people felt so overwhelmed by the sheer noise of others exercising their constitutionally protected freedoms.

Increasingly, this dynamic produces an exchange in which one person does their utmost to promote a message while another person, the intended recipient, does their utmost to ignore that message. As Janis Joplin never said: “Freedom’s just another word for making a nuisance of yourself.”