Greg didn’t think it was a coincidence he shared his given name with the famous movie star who inspired his best idea to date. Like Gregory Peck posing as a Jew so he could report on what it’s like to get the short end of the cultural stick, Greg thought he could work up an amazing exposé by posing as a front line health care worker. Greg wanted to know what it was like to live with the exhaustion, the stress, the heartache, of working as a medical professional in the middle of a global pandemic. An opportunity like this doesn’t come every day, you know.

Greg had stolen hospital greens from a cleaning truck parked on Bond Street on the east side of St. Mike’s Hospital, and his buddy, Gordy, a digital artist, had agreed to make a fake ID. While Greg posed for his fake employee mug shot, Gordy confessed that Greg’s scheme made him feel uneasy. Gordy thought it was unethical. Greg told him to chill. It was a standard journalist thing, going undercover to find out what it really feels like to be on the front lines. Besides, he said, it’s not as if I’m gonna do anything medical; I’m just there to feel the vibe. As Gordy laminated the fake ID card, he made Greg promise not to touch any patients and, for god’s sake, don’t catch anything. Greg promised, then went home to binge watch old episodes of Grey’s Anatomy so he’d be up on his medical jargon.

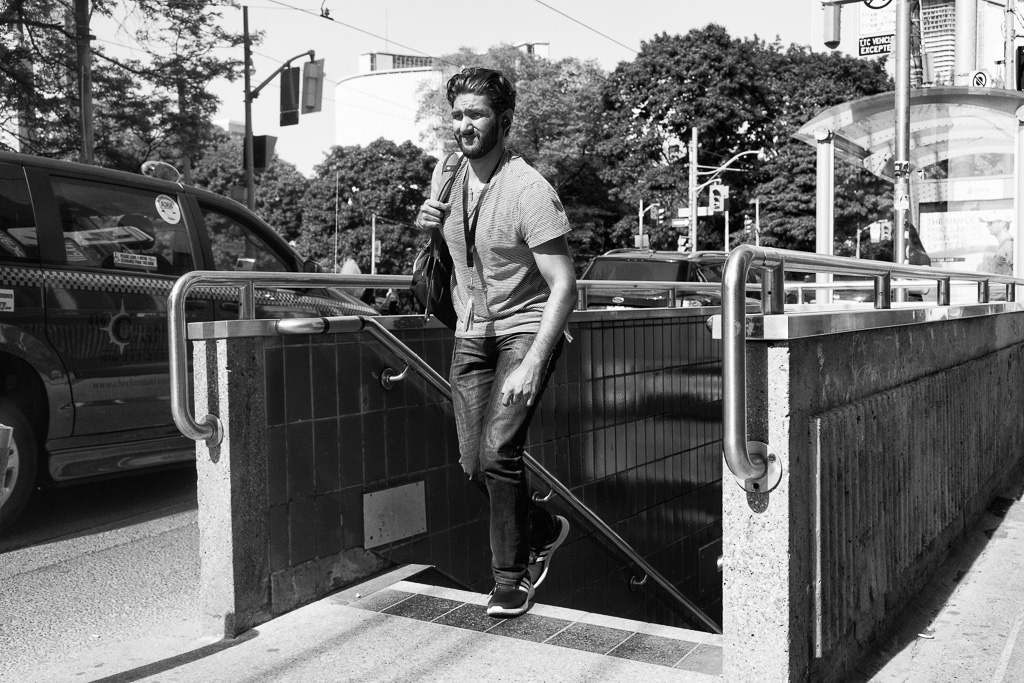

Greg rationalized his plan by saying it was in the public interest to know about the suffering of health care providers, but he had to admit that he was equally drawn by the desire to know what it felt like to be called a hero. Normally, nobody would ever call a schmuck like him a hero. He heard how people leaned out their windows at night and banged on pots. And he heard how newscasters talked about their extraordinary sacrifice. Who wouldn’t want some of that recognition? On the subway for his first shift, ID dangling at the end of his lanyard and glasses steaming above his blue medical mask, he couldn’t help but notice the way people looked at him and the way it made him feel. He would have to make a note of this for his exposé. As he got out at Queen Street, a couple guys patted him on the back and thanked him for his sacrifice. He said thank you back and told them how he was just doing what anybody in his position would do.

Walking east along Queen Street toward the hospital, Greg kept his head low, trying not to draw attention to himself, especially as he got close to the entrance where a group of security guards stood in a row, arms folded and looking stern. When he crossed Victoria Street, he noticed the news van with the dish on the roof and big logo on the sliding door and the cameraman and the talking head with perfect hair and microphone. This wasn’t the only news van. There was a whole row of them lined up behind the first van. And a whole row of reporters standing along the curb opposite the row of security guards.

The two rows—reporters and security guards—formed a gauntlet and running the gauntlet right down the middle of the sidewalk was a group of protesters shouting and waving signs. At first, Greg had no idea what the protesters were going on about, but as he got closer, he saw they were a bunch of whack-a-doodle conspiracy theorists who said the whole thing was a hoax perpetrated by the global elites to keep ordinary people under the boot. They were spreading the disease with cell phone towers. The whole thing was a big eugenics project. It was the product of covert biological warfare.

The marchers drew up to where Greg stood and they stopped. Greg was astonished at the number of marchers who needed major dental work. Another observation for his exposé. Somebody in the back yelled how health care workers were complicit in spreading the disease. That just set Greg off. He couldn’t help himself. He had to respond. It was a matter of honour.

Greg tore into an impassioned speech about being an ordinary working guy who suddenly found himself with a difficult choice: either play it safe and sit at home collecting welfare, or step up even though that meant risking infection. Well, virtually every one of his colleagues had chosen to step up and take the risk. Not because they’re special. But because it’s the right thing to do. What’s not the right thing to do … And Greg lit into the marchers, calling them ignoramuses and selfish buffoons, and giving all the news services terrific sound bytes. But Greg wasn’t about to go easy on the news services either, taking a step towards one of the cameras and pointing a finger at the lens and calling them irresponsible for their hackneyed bothsideism which tried to give legitimacy to a side populated by ignoramuses and selfish buffoons and …

Greg reached the climax of his set piece when a fist magically emerged from the crowd and flattened him. Stars burst like fireworks in a black sky. The copper taste of blood seeped down the back of his throat. He heard the sound of crunching bone and, afterwards, as he lay on the sidewalk, he felt a throb across the left side of his face that made him wonder if maybe rodents hadn’t burrowed into his head. Christ, he thought, I’ve taken things too far.

A police officer tackled the owner of the fist and two orderlies attended to Greg while one of the security guards ran off for an ice pack. The news services did what news services do best and made an indisputable record of events from seven different angles. When the police officer had cuffed the assailant and read him his rights and left him to cool off in the back seat of a cruiser, he returned to the scene and knelt beside Greg. The more the police officer leaned in to him and spoke in sympathetic tones, the worse Greg’s face throbbed. When the police officer explained to him the charges against the assailant and how they’d like Greg to make a statement if he was feeling up to it, Greg waved the man off. He struggled to his feet and wobbled a bit, then, unrecognizable beneath his purple eye and swollen face, he turned to the same camera he had accosted only minutes before, and said he bore no ill will for the man who punched him in the face. These are difficult times for everybody. For extra effect, he spat blood into his shirt sleeve. I’m sure that guy’s got it tough already. The last thing he needs is criminal charges against him.

Greg hoped that would diffuse the situation and give him a chance to slip away before someone recognized him. But it only made things worse. He heard one of the security guards shout that he was a hero. And one of the news people started rehearsing lines in front the camera: Now, folks, this is what real heroism looks like. Only moments ago …

Someone called for his name. Someone else asked what department he worked in.

Greg wanted to run away, but his legs felt like rubber bands. He wanted everyone to leave him be; he’d be fine if he sat here alone for a while. He wanted to tell them all to fuck off. But he couldn’t do that. One thing he knew for certain is that a real hero doesn’t tell his admirers to fuck off.