My post yesterday featured a blank-eyed Roman bust and dwelt upon the old cliché: the eyes are the windows to the soul. I wanted to know where the saying comes from and, after a cursory search online, I landed on a web site called phrases.org.uk. I have no idea if it’s a credible site and it doesn’t really matter. For my purposes, what does matter is that it offers an interesting illustration about the malleable nature of word usages.

The web site suggests that an early source for the idea that the eyes reflect a person’s soul is the Roman writer, Cicero, who was a contemporary of Julius Caesar. As you might expect, Cicero’s native language was Latin. But when the web site tells us this, it substitutes an asterisk for the letter “a” and gives us L*tin instead. Presumably the web site does this so that search engines don’t flag it as somehow derogatory towards a group of people. Not the group of people who lived 2,000 years ago and spoke the Latin language. Another group of people still alive today.

I think it’s reasonable to say that the word “Latin” accurately describes a dead language which people formerly spoke on what is now the Italian peninsula. “Latin” is not a word English people made up and imposed on another people; it is a word its native speakers applied to describe their own language long before English emerged as a distinctive language. However, as context changes, we find other meanings grafted onto the word “Latin” and we feel compelled to make adjustments to our usage.

Shifts in meaning happen all the time but most go unnoticed except by lexicographers. The shifts that attract our attention are the ones that do harm. The “N” word, for example, with its Latin etymology tying it to the Roman word for “black”, is now impossible to utter without racist associations. People twist themselves into knots over its appearance in literature and pop culture. Think Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn and Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction.

In the spirit of doing unto others as I would have others do unto me, I’m inclined to give Mark Twain a pass. He had no way to anticipate how the prevailing culture would overtake the “N” word. It’s important, too, to note that his usage appeared in a context that aimed to present a Black man as a flesh and blood character who warranted the reader’s empathy. I would hope for the same consideration in my own writing. I have no way to anticipate how context may overtake my own usages and end up casting a shadow across my benign intentions.

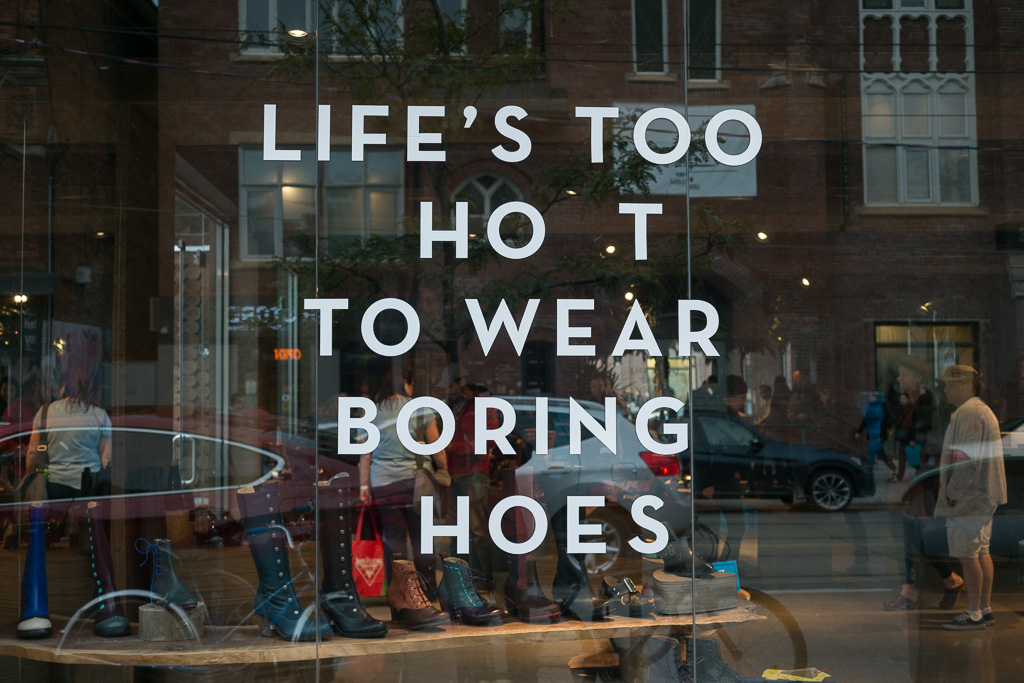

The concern nowadays is that humans no longer assess our usages. Bots on social media sites identify offending words and suddenly we find ourselves shadowbanned or our accounts temporarily suspended. Despite all the techno-optimism wafting through the air these days, there is no such thing as an algorithmic solution to the problem of context. The bots run roughshod over everything, so we protect ourselves in advance by inserting asterisks, dashes and numbers. What the f*ck? Oh my g-d! Quentin is such a sh1th3ad.